Laverne Cox is an African-American transgender individual who has become a breakthrough, history-making artist…and a household name.

An actress, reality television star and producer, and LGBTQ advocate, Ms. Cox became the first openly transgender person to be nominated for a Primetime Emmy Award for her portrayal of “Sophia Burset” on the Netflix television series Orange is the New Black. She’s graced the cover of Time magazine, and became the first openly transgender individual to have a wax figure of herself at Madame Tussauds.

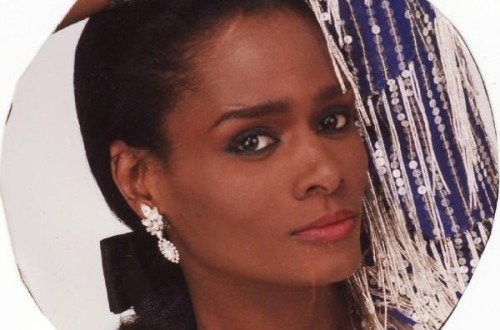

But before there was Laverne, there was Tracy “Africa” Morgan. She first exploded on the scene in the 1970’s as the first-ever Black transgender model. But sadly and unfortunately, her career went into free-fall…and crashed like a plunging meteor. This occurred after she was exposed as being a transgender person.

Ms. Morgan is now 63. In her recent in-depth interview with New York Magazine/The Cut, she discusses her personal challenges, her rise to stardom…and her ongoing battle to conceal her true gender in a not-so-understanding and accommodating era in the business.

The publication states, “To be Black and from Newark (New Jersey) in the mid-1970’s and get plucked from a model casting call for Italian Vogue by Irving Penn (the African-American photography icon and visionary)—it was the kind of success story that was unheard of, especially for someone like her. She was signed by a top agency, photographed multiple times for the pages of Essence magazine.

“She landed an exclusive contract for Avon skin care, another for Clairol’s “Born Beautiful” hair color boxes: No. 512, Dark Auburn, please. (Morgan claims that Clairol told her that it was its “hottest-selling.”) She went to Paris and became a house model in the Balenciaga showroom, wearing couture and walking the runway twice a day.

“Norman was never as big as Iman, Beverly Johnson, Pat Cleveland, or the other models of color breaking barriers on international runways or on the cover of Vogue. But she was riding the wave. It was more than she could have hoped for when she was a kid in (Newark) New Jersey. Back when she was a boy who knew that, inside, he was a girl.”

2015 is radically different than 1975: you have the success stories of Laverne Cox and Caitlyn Jenner, for example. “This kind of cultural acceptance makes it easy to lose sight of just how dangerous it was 40 years ago—and still can be today—for women like Norman to just walk down the street,” the publication continues. “Fear of harassment from both police and civilians was constant. To live one’s life openly as a transgender woman, let alone as a black trans woman, simply wasn’t done. The only option, really, was to ‘pass’ in straight society.”

Morgan relates that she felt like a girl—even though she grew up as a boy. “’It seemed like I was living in the wrong body. I always felt female’.” According to Morgan, it was extremely challenging trying to cope with and make sense of her inner turmoil.

In that interview, Morgan says that “being effeminate” was a continuing source of conflict between her parents. While her mother was accepting, her father believed he could change her. “’He tried everything he could. He bought me boxing gloves and was trying to teach me how to box. Kept hitting me on one side of my head’.” Soon after the last fight when she was six, her parents split up and her father moved out. And according to Morgan, after junior high school, her father was no longer a factor in her life.

After high school in 1969, she gathered the courage to tell her mother. She states that her mother told her that she’d always known—and that she accepted her for who she was. “’She just opened her arms, gave me a big hug, and said that she knew, she was just waiting for me to come to her,’ says Norman. ‘I had a moment where I realized what they mean when they say unconditional love’.”

As she frequented clubs with transgender persons of various ethnicities, she seriously began transitioning. Recalls Norman, “’They were absolutely breathtaking to me, and I knew that I was in the right place. Eventually, I got up enough nerve to start asking questions. And I finally found someone who told me where this doctor was’.

“’You would pay in cash and come back the following month and get another shot,’ says Norman. Her breasts began to grow, reaching a B cup, and, she says, ‘I was slowly melting,’ losing weight without trying, perhaps because of the hormones or perhaps because she was happier. Or perhaps it was the acid-laced punch at gay dance mecca Paradise Garage. ‘They warn you, ‘The punch is spiked’ and it just went—psheeeww!—right over my head. The next thing I knew I was on the dance floor until the morning: This is the best punch I ever had’! The rest came off without conscious effort. ‘Losing weight was being active in the summer, learning how my body worked. Having sex.’ She laughs. ‘That’s an activity’.”

According to Morgan, the friends who assisted in her transitioning warned her exactly how vulnerable she’d be in the industry. “’They told me, ‘Just go in, do your work, and leave. Don’t worry about being invited to dinner with photographers, don’t stay late by yourself with photographers, don’t go to big giant parties by yourself with photographers. Just tell them no thank you and come home’.”

With changing clothes in public being part of the job, how did she pass? “’Duct tape becomes a girl’s best friend’,” she says, slyly. ‘I had to do other things, yes. I’d like to keep some things private’.”

So after a high-flying career that included being a house model for an elite and celebrated Parisian showroom, coveted contracts with Avon and Clairol, and gracing the pages of Essence and Italian Vogue, just what caused the precipitous and jarring fall of Tracy “Africa” Morgan?

After crisscrossing the country for catalogue shoots–including Italian Vogue— she landed a major gig with Essence. It was at that particular shoot where she’d have her first close call.

According to that New York Magazine/The Cut interview, “During a break in the shoot, a makeup artist pulled Norman to the side and said that he knew what was going on with her. Maybe he noticed how nervous she was, or how large her hands were and how she’d cross them just so to make them appear smaller. He said, ‘Don’t worry. I think you’re beautiful. Just be natural’. It was worrisome that he noticed her secret, but he seemed to have good intentions, and his encouragement actually helped her relax. ‘I just started being myself during the shoot’, Norman says. When Norman got the call some six months later for another Essence shoot, she knew that the makeup artist had kept her secret.” However, more than likely, this “narrow escape” triggered her career’s rapid descent.

Now, fast forward to 1980, at an Essence holiday shoot, which was moving along quite nicely.

Then, on the third roll of film, a certain hairdresser who was at most of Morgan’s Essence shoots, enters the set. He was the one who always asked her questions, grilling her. “Norman thought she’d done enough to throw him off the trail of her true identity. Still, when he walked in that day, she lost her concentration. ‘For some reason it felt negative’, she says, ‘The whole situation felt negative to me’. According to Norman, the hairdresser spoke with Taylor (Susan L. Taylor, Essence editor-in-chief from 1981-2000) and then Taylor stopped the shoot, saying: ‘I think we have enough’.”

The hairdresser is now deceased and Taylor didn’t respond to interview requests, according to the publication, which also reports, “Taylor didn’t say anything explicit to Norman then—or ever. And it’s possible that Norman misinterpreted their interaction. But she doesn’t think so. The next day when she called her agency to find out if she had any bookings or go-sees, they said no. ‘All I know is that my work stopped that day’.

“Norman claims she was not paid for that last Essence job, and the pictures were never used. She says she contacted Taylor to see if she could at least have copies of them, but ‘she said none of them came out good’, Norman says. ‘Later I heard she threatened to sue the agency for false advertisement. But the agency didn’t know about me, either’.”

At some point though, one of Morgan’s industry friends confirmed that she had indeed been outed. “’It goes through the grapevine really fast. Really, really fast. I kind of upset the fashion world for a while’, Norman says. None of the girls she’d modeled with would speak to her. ‘I had many black female models that I took jobs from super-angry at me’, she says.”

In the interview, Norman confesses that she “was depressed about not having work but also angry that no one would actually say why. ‘I was upset that nobody confronted me with the truth’, she says. ‘I guess that’s maybe because they were afraid of lawsuits, but I don’t know if I would’ve had the frame of mind at that time to try to sue people. I just felt so upset about it because it was my people and my community that did this to me. The black community and the gay community’.

New York Magazine/The Cut states, “It’s taken Norman years to understand that perhaps Taylor and her agency felt betrayed or lied to. But the reaction itself is proof of why she had to keep her secret. Being out was never an option. (Morgan says 🙂 ‘I’ve always said that the person that walks through the door first leaves the door cracked. There was a perception that a transgender woman couldn’t be passable and work in fashion magazines and land contracts. I proved that wrong. I left the door cracked for other (transgender people) to walk though’.”

And then, there was a Laverne…

Great stuff Wyatt. Get her as a guest on your show.

Thanks, Anthony! I’m working on it.

You may want to change her name to Tracey Norman, not Morgan….

“But before there was Laverne, there was Tracy “Africa” Morgan. She first exploded on the scene in the 1970’s as the first-ever Black transgender model. But sadly and unfortunately, her career went into free-fall…and crashed like a plunging meteor. This occurred after she was exposed as being a transgender person.

Ms. Morgan is now 63. In her recent in-depth interview with New York Magazine/The Cut, she discusses her personal challenges, her rise to stardom…and her ongoing battle to conceal her true gender in a not-so-understanding and accommodating era in the business.”